My parents have repainted the house that I grew up in. The walls are so pristine now, they do not flaunt the staunch tattoos of another time – pen scribbles and cello tape marks, scuffs and chips from things that moved around in another time. The furniture is mostly new too. My old desk was handed down to my cousin, the old dining table is with an uncle. There are things that were there when I was around, of course there are. The kitchen table has marks from when I left a burning candle without a holder. The dressing table in my room still has the old box with cards and gifts from those I once used to speak to, every single day. A bit of the old and the new in every room – like my parents and Miss A. Who I once was, who I am now, bits and pieces cobbled together to make a person.

The garden, it is overgrown in some parts and bare in others.

“There was a swing here,” I tell Miss A. “And a garden bed here and roses over there.”

I spent years playing hopscotch around the pathways and I used to chat into the evening with the best friend. She is gone too now, but I did get to meet her, we sat on the same step after all those calendar pages, we talked of the same things we did when we were younger and when the world was this strange place down the highway. She went home after that and as I waved goodbye, I knew I was not staying either.

Homes are not permanent. Only the times spent there are. That is the way it is for most things in life but why would childhood teach you such a harsh lesson!

My parents still talk about the day in the early hours of dawn. Outside the sky is black but a bit of pink is creeping in from underneath the doors, a bit of light is pushing against the curtains. They talk about the day that is yet to be and the day that has since been. About the hibiscus in the gardens and the coconuts that need to be stored in the spare crates. About how the old water tank will need a new pump set soon. The winter outside their window and how two quilts aren’t enough because the weather forecast was wrong yet again. They complain of how the new teapots these-a-days have bent handles and how they need to stock up on some kind of light bulbs. About the squirrels raising a ruckus in the garden, and the back tiles that need scrubbing. It is a soft muffle, their voices, laced with sleep, in the early hours of an incorrectly forecast winter morning

Then they switch topics and talk of politics and cricket and mull over election results in some far flung north eastern state. The tea boils over in the meanwhile, in the teapot with the bent handle, and the cups go clink-a-clink. There is a scraping sound as the biscuit tin is opened and the door to my darkened childhood room opens just a little bit.

“Do you want tea?” they whisper. “It is cold outside.”

“It is 5 AM,” I grumble and disappear under the blankets.

“I could get you tea here,” my mother says. “You could go back to bed after you drink it.”

“I am in bed,” I say. “And I don’t want the tea.”

This has not changed, this bit, we have had this dialogue for years. She walks away closing the door behind her and suddenly I want the tea. But then sleep, blessed and warm, beckons and it remains unsaid and discarded, this morning wish. Tomorrow, I tell myself, tomorrow is when I shall say yes to the tea.

Like so many childhood things, like so many grand plans that never make it to the cusp of the day, that tomorrow slips away too. Some things are meant to be done later, some things come postmarked with a future date.

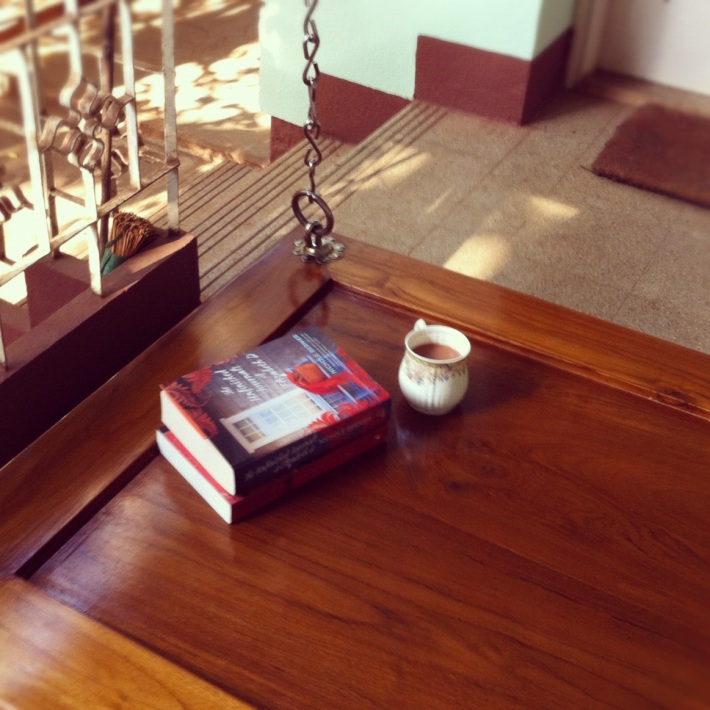

The garden is sleepy and agreeable in the afternoon. The air is woody and has a tang – it it smells of the cold in the way only my hometown does – it is heavy with the memories of a thousand past afternoons. The winter sun is at once plump and meagre, a marvellous contradiction of sunlight. I fall asleep on the swing this time, and the road, it stays quiet like it did when I was a child here. A bird chirps. A tap drips. A door bangs three houses down. I fall into a dreamless sleep because when you are home and safe, you do not need any other visions.

Somewhere in the middle of the nap, I wake up to find myself covered with a blanket. Dregs of sleep in my eyes. The street still a quiet child, waiting to be given the go-ahead to talk again.

“Do you want tea?” my mother asks. She has, I suspect, been staring at me all along, waiting for me to wake up.

“Yes,” I say and her face lights up.

She brings me a cup almost immediately and we drink tea on the porch, me on the swing, still under the blanket, she on the side chair. Occasionally the swing bumps into her chair. There is nothing else to do on afternoons like this. And so we say little and yet there is such a crowding of memories.

A week later I pack my bags and Miss A’s and we cry a little bit on that same swing. There is so much to say when you part for a while, there are so many incomplete stories that beg to be finished when you open the gate to leave. Instead I joke about the garden and I fuss over the luggage. I try to pretend I am not leaving the house behind. It knows though, it has seen my pattern over the years. So I crane my neck and try to gather in the walls, the jasmine creepers, the errant hibiscus, the mango trees, the faithful swing, the neighbours with wet eyes and wrinkled palms – they all wave back, they do not break eye contact with me. It knows, like I said, the house, it knows that I will go past the bend in the road and not be back just yet. My heart sags, my throat hurts and I do not dare speak.

If they had told me that goodbye was an essential word in the vocabulary of grown-ups, I would have asked the house to hide me in one of its many forgiving nooks, I would have created a tree-house in the old branches, I would have parked inside a tent under the beds. But I am gone now and the house has stayed behind.

And one day, I shall see it again but that day is not today.

There were so many days in my childhood when I wanted to grow up and do things. Big people things, adult things, things that extended beyond the fence and the rusty gate.

Someone opened the gate and it cannot be shut again, I think my childhood escaped when I was growing up and I did not even notice.

And now, I have a key and I can go where I want to but that damned, damned key – I cannot lose it even if I want to.

Homes. Not permanent. Time. Permanent. The twitch in my heart. Eternal.

Recent Comments